German SS Kommando - Hans-Dieter Cieslewicz

The story of the most intriguing Soldbuch I have ever encountered…

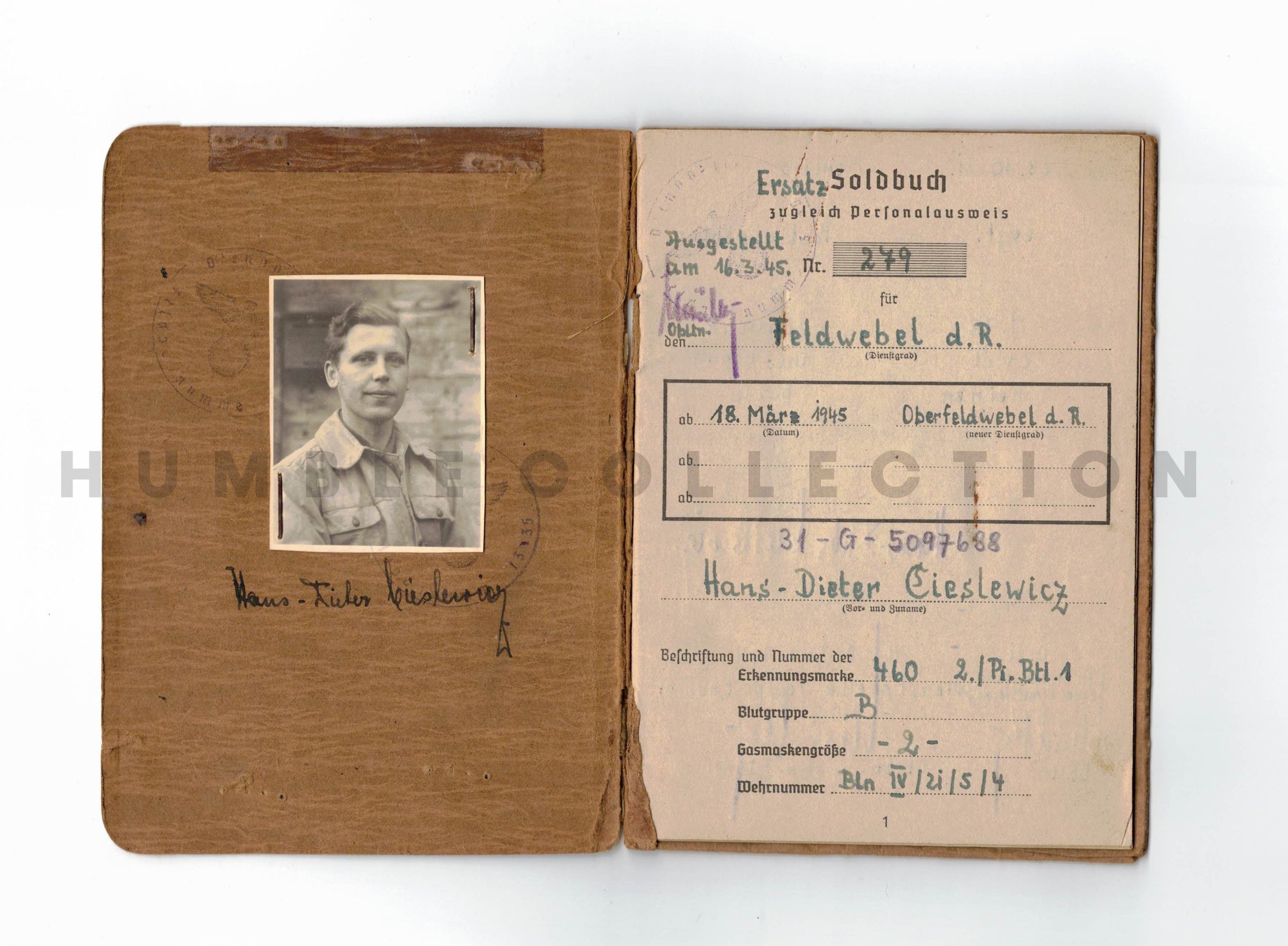

Photo of Hans-Dieter Cieslewicz from his Soldbuch and image of Cieslewicz during the raid to rescue Mussolini (Credit to History Channel tv show - "History's Raiders" - episode "Hitler's Commando, Otto Skorzeny")

This year will mark the 80th anniversary of the Gran Sasso raid to rescue Mussolini (Operation Eiche), which took place on 12 September 1943. I want to share with you the Soldbuch to one of Skorzeny’s sixteen SS Jäger Btl. 502 commandos that took part in the glider assault that day.

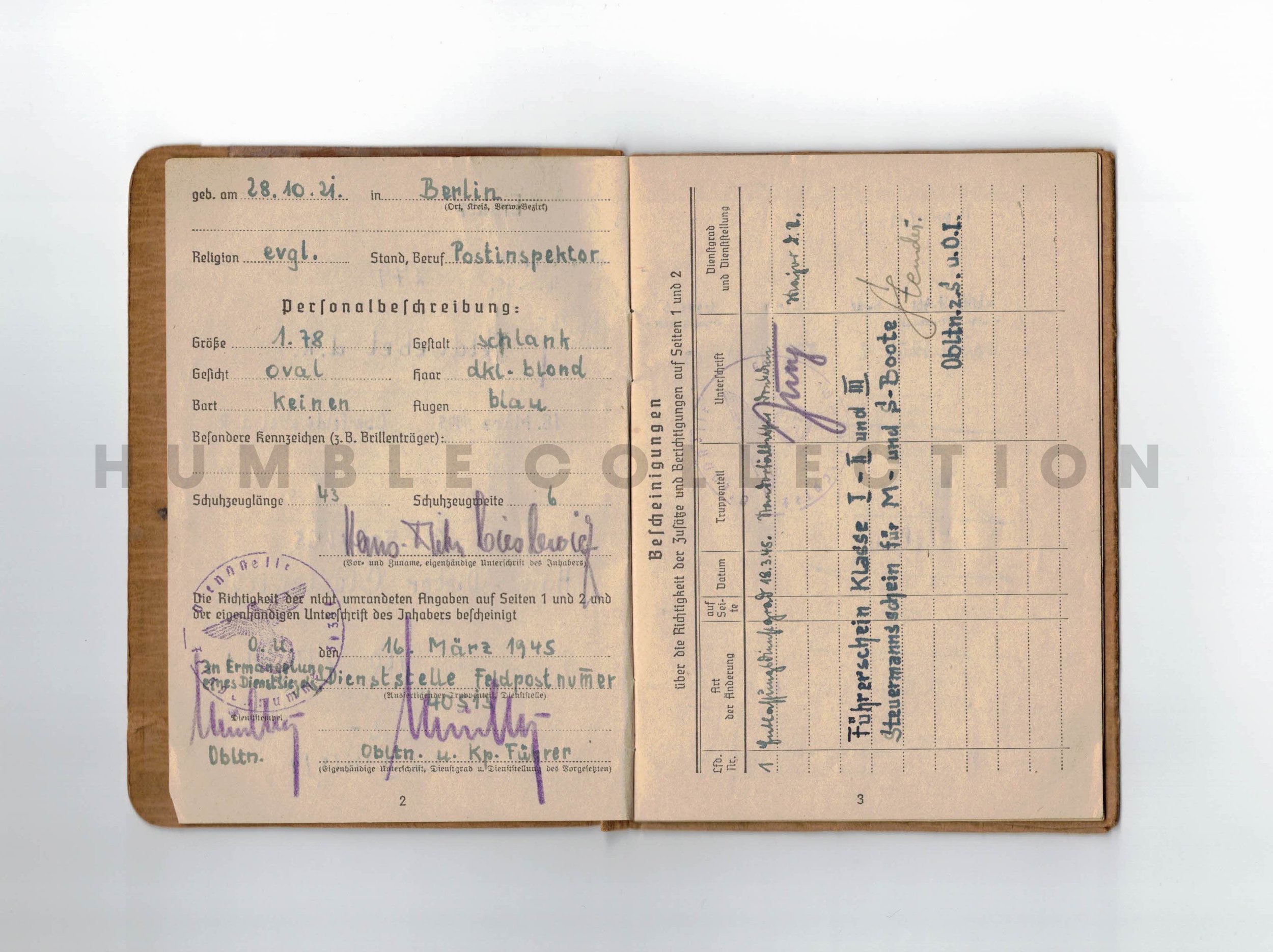

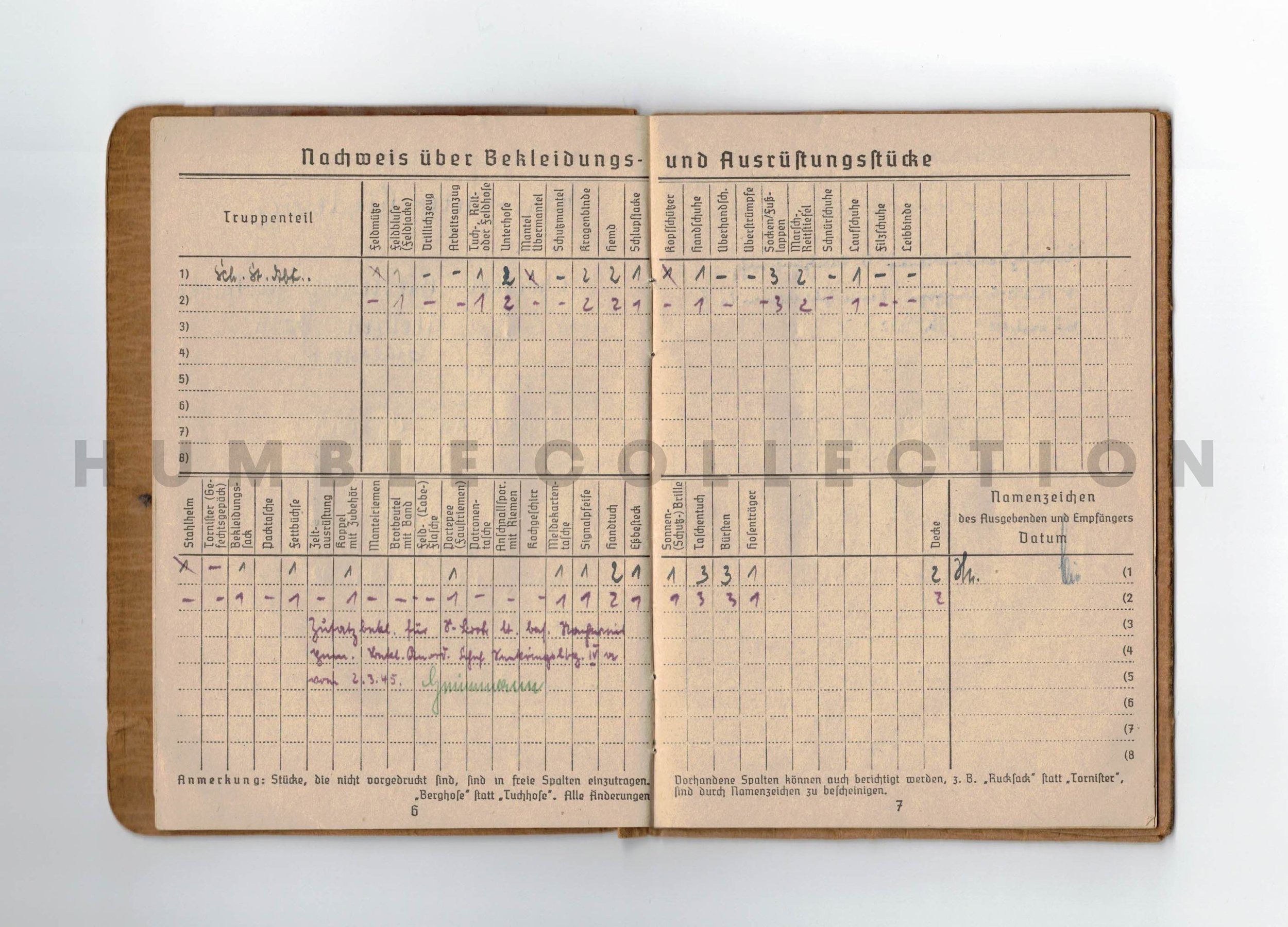

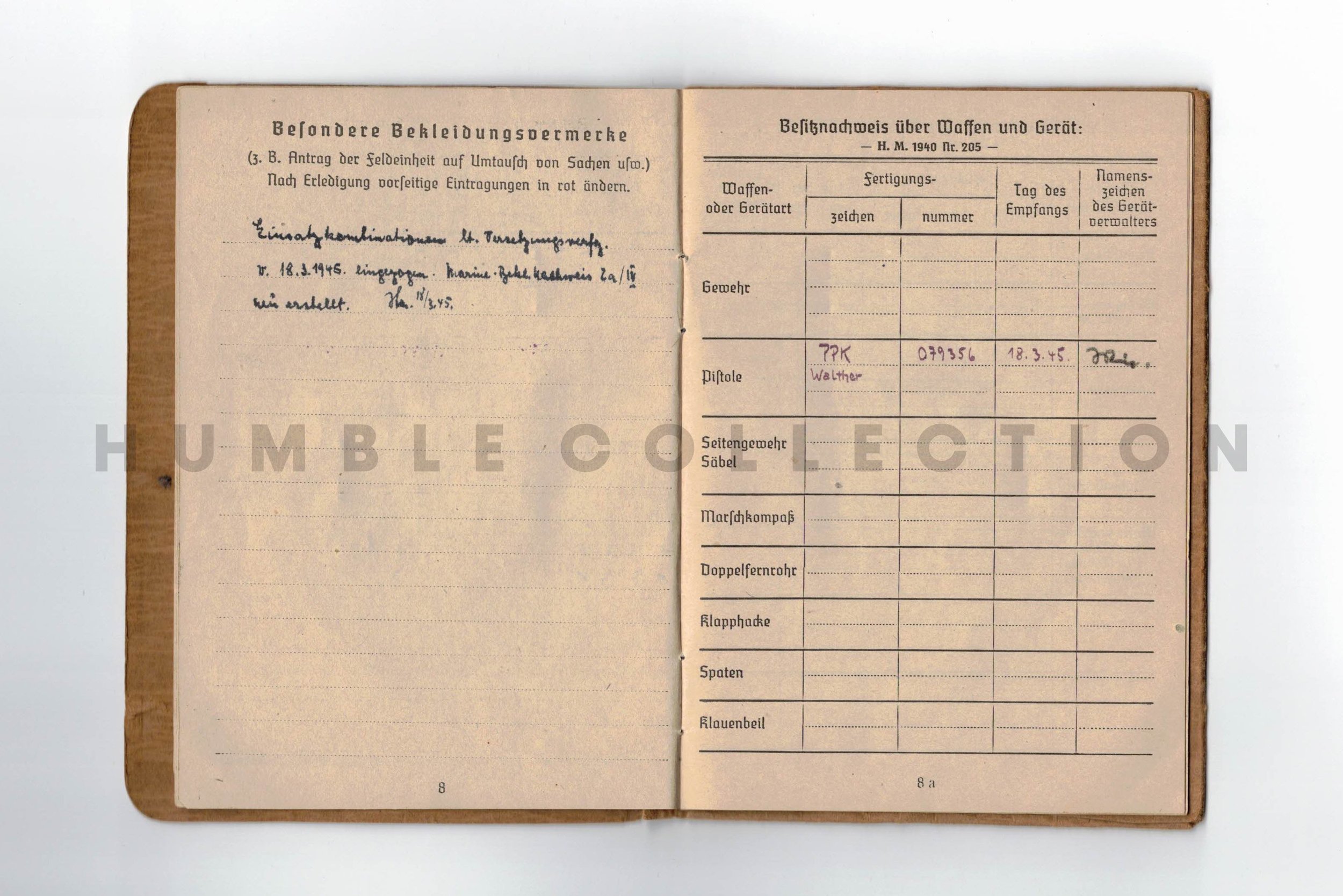

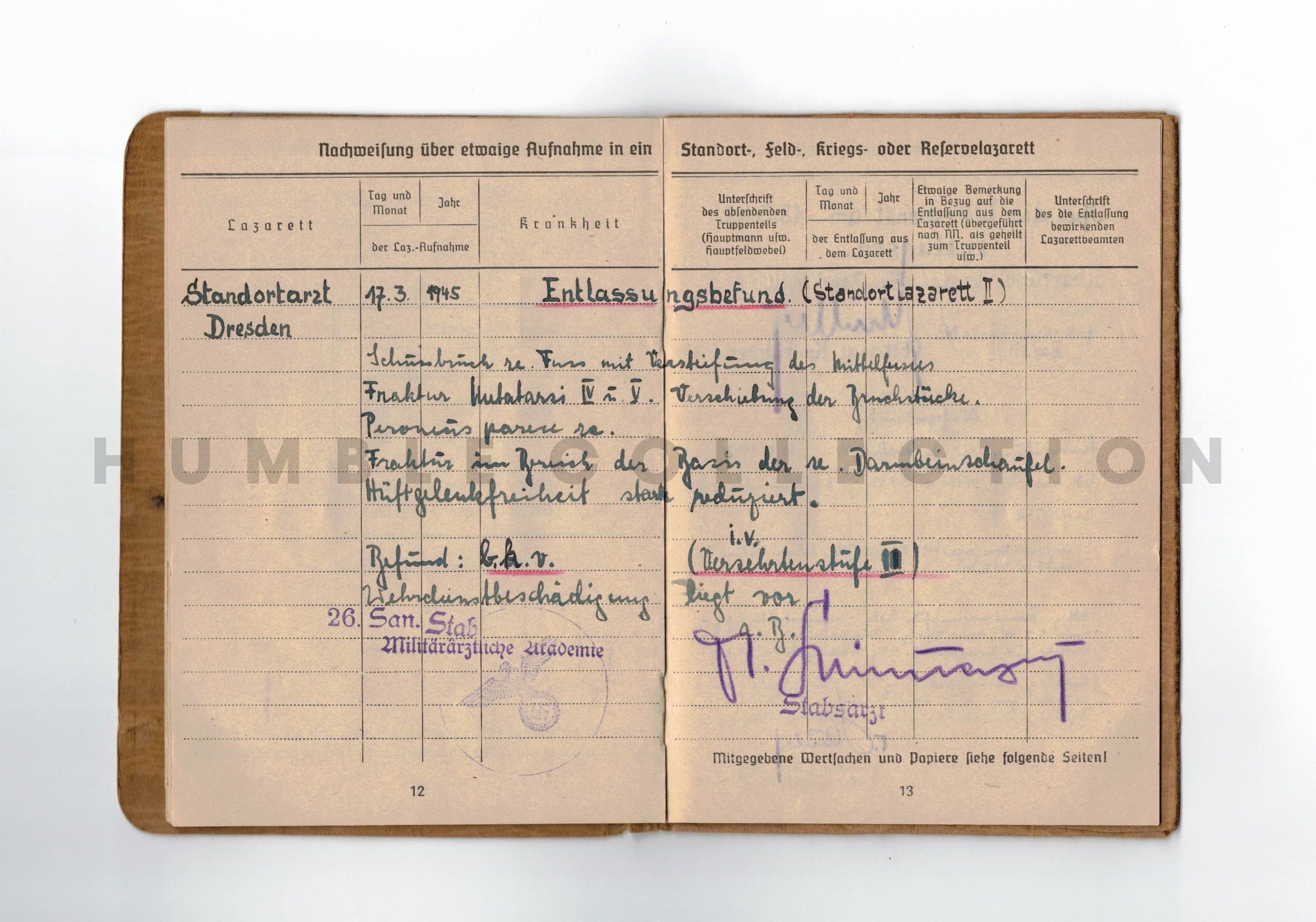

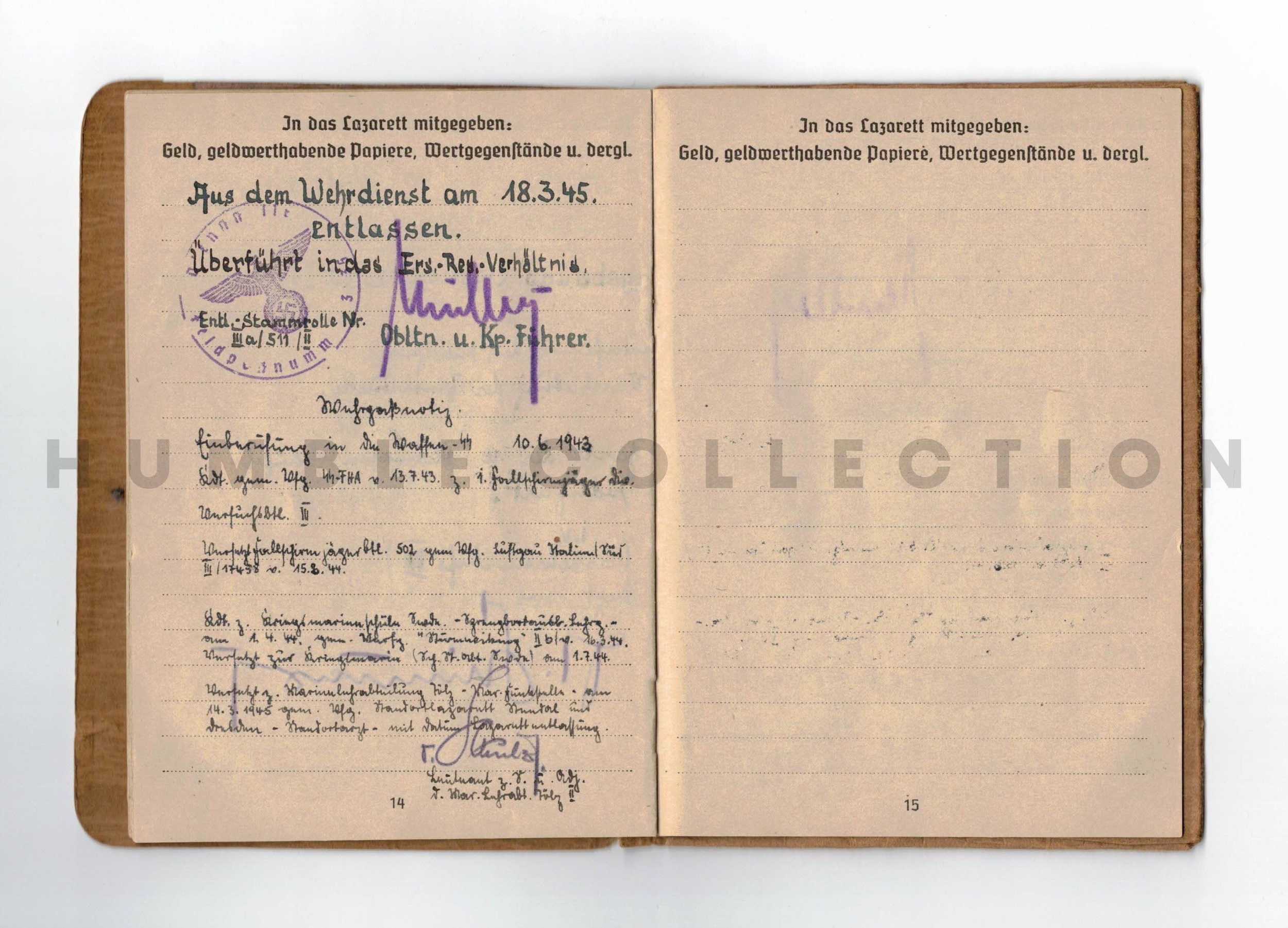

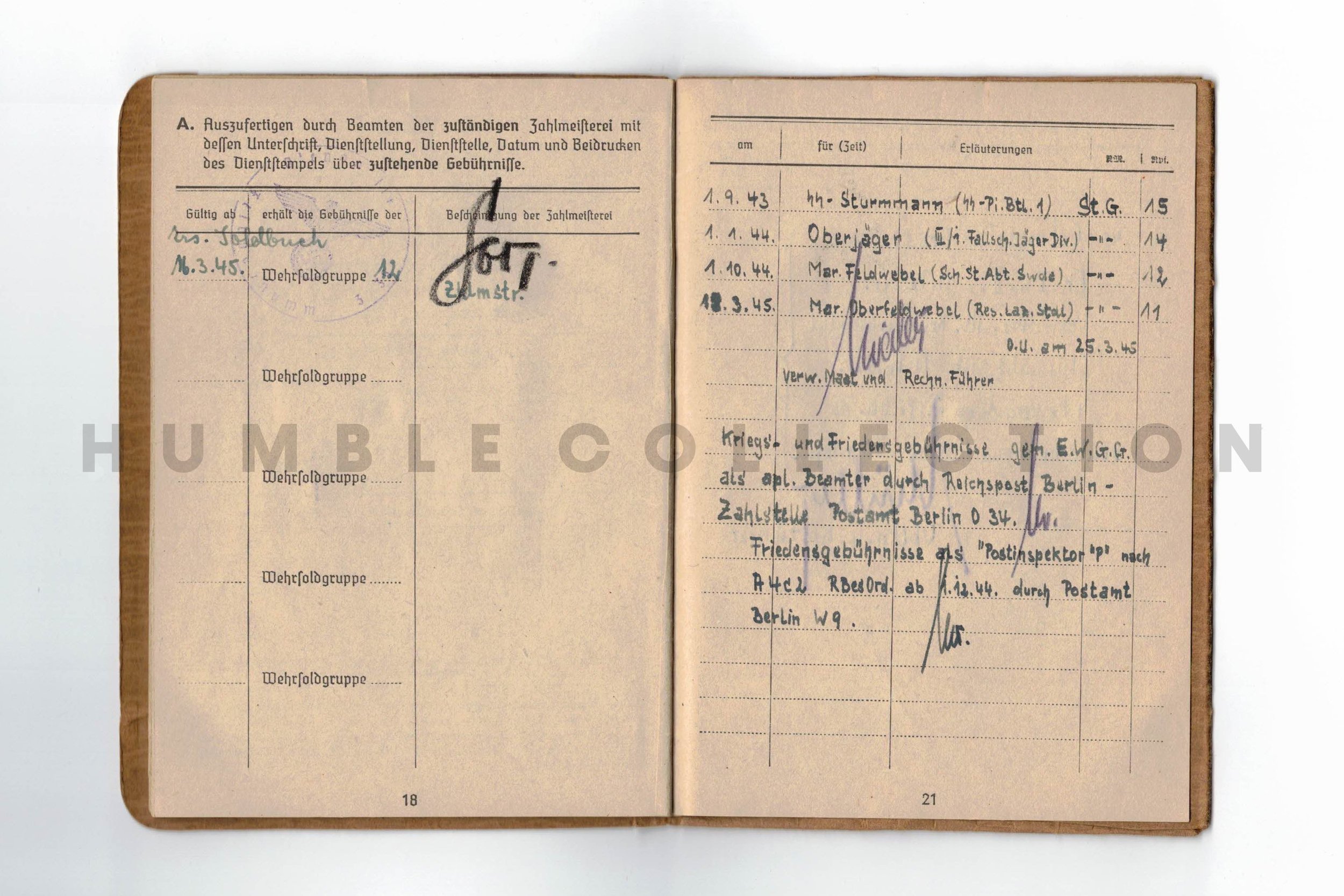

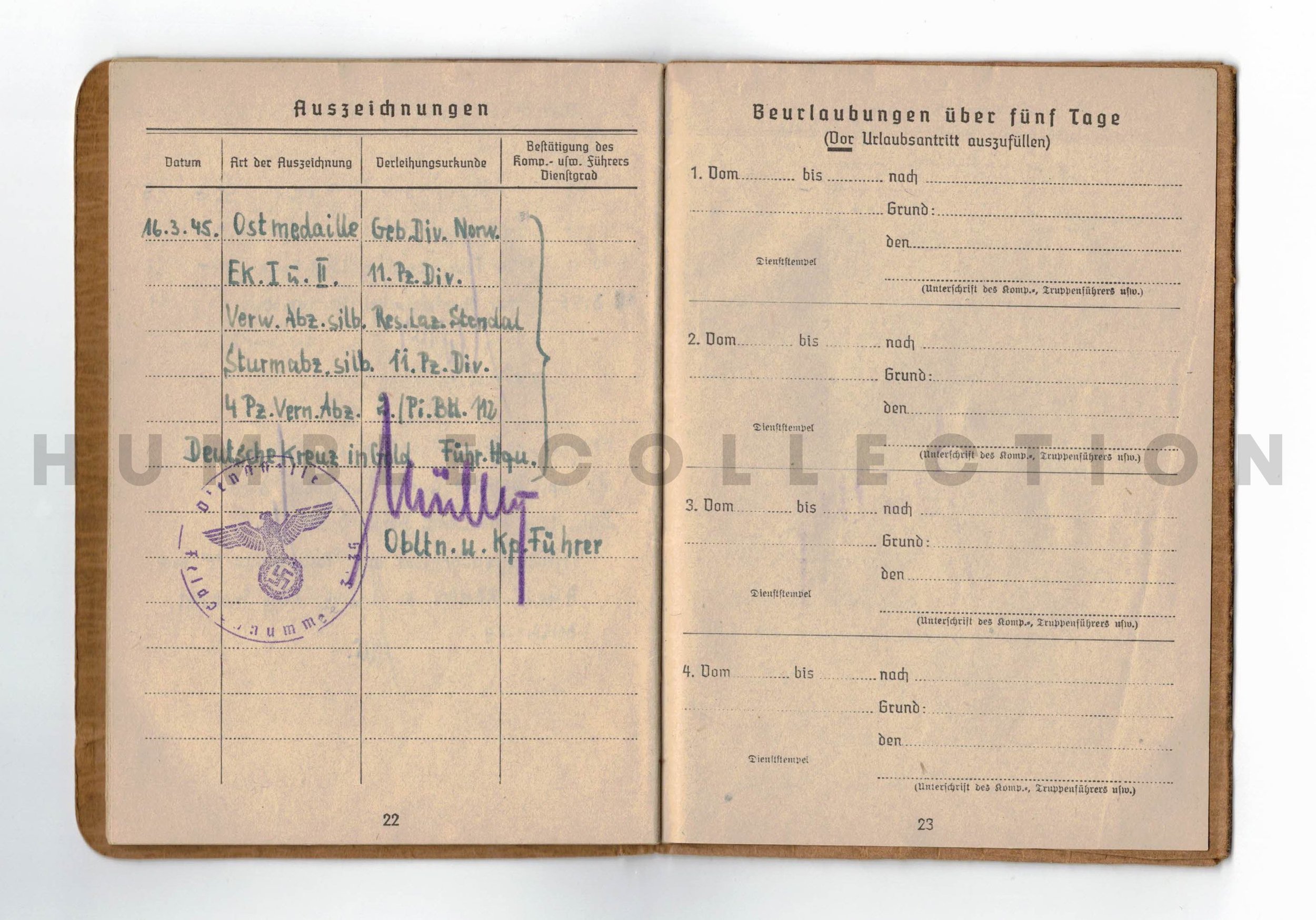

This fascinating Soldbuch to Marine Oberfeldwebel der Reserve / SS-Unterscharführer Hans-Dieter Cieslewicz might be easy to overlook at first glance. It is a standard Heer (Army), late-war replacement Soldbuch that was opened on 16 March 1945. There are several entries that at first might seem confusing, if not impossible to understand or preposterous, without context from extensive research. It shows that he fought with every branch of the German military (Heer, SS, Luftwaffe, Kriegsmarine) and was awarded several very impressive medals – including the German Cross in Gold and 4 tank destruction badges. Most likely, he was awarded the German Cross in Gold for the Gran Sasso raid.

What follows was the result of almost two years of research. For a Soldbuch collector, this is about as hard as they come for a research project.

Many commando units like the Brandenburgers and K-Verband purposefully made these documents secretive due to the assignments of their operatives. For example, the U.S. Military Intelligence Division published a booklet during the war entitled, The Exploitation of German Documents. Under Section 1-a.(4) entitled “False Names” it states:

“In rare cases unit identifications may be shown in all official papers under false names, usually intended to conceal an intelligence or sabotage organization. In Tunisia, for example, it was found that paybooks [Soldbucher] showing the "Krad-Schtz.Ers.Btl. 4" as the affiliated replacement unit ("zuständiger Ersatztruppenteil") really belonged to men sent out by the Lehr-Regiment Brandenburg.”

Cieslewicz’s Soldbuch has a couple “cover” units mentioned as well as Feldpost stamps that have been purposefully altered and concealed. Several dates and missing information in the Soldbuch (like rank of SS-Unterscharführer not being mentioned) were intended to conceal his service before 1943, which we know existed from German archive material. The “cover” units were intended to conceal his involvement in the Gran Sasso raid to rescue Mussolini and a failed operation in early 1944 to assassinate the Allied theatre commanders, Generals Mark Clark and Harold Alexander at the Anzio beachhead in Italy.

I think that anyone who is interested in researching Soldbücher will enjoy this story about the incredible military career of Hans-Dieter Cieslewicz and will appreciate the amount of research it took to piece together this complex puzzle of information. Many segments that I am posting came directly from Wehrmacht Awards Forum member Stormfighter’s original research and post from January of 2013, as well as research from books and material from government archives.

Lastly, I should put out a disclaimer that I do not expect anyone to read all of the information that I have written, unless you find this research as interesting as I do. Hans Cieslewicz’s story could be written into a book. I find it incredible. But even with the vast amount of research that I have done, I feel like I have only scratched the surface into the full story. For all of the questions that I have found answers to regarding his Soldbuch, now I have so many more questions about Hans-Dieter Cieslewicz’s war experiences and fate after the war.

Early Years (1921 – 1940)

A handwritten Lebenslauf (Resume) that Cieslewicz wrote on 19 July 1943 within his personnel file on microfilm housed at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland, provides information about his life from his birth through 10 June 1940, when he joined the Waffen-SS.

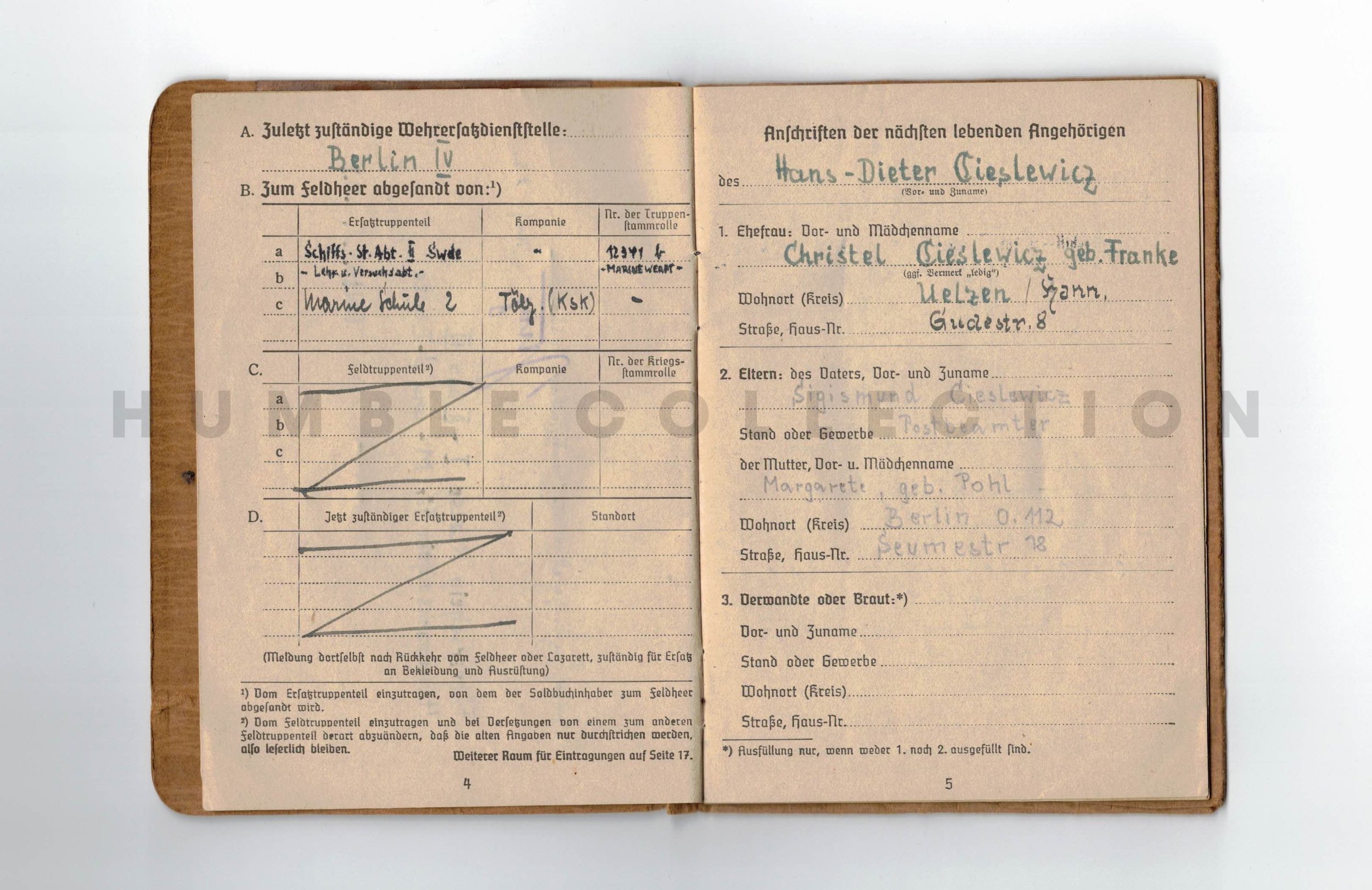

Hans-Dieter Cieslewicz was born on 28 October 1921 in Berlin, where he resided at Seumestrasse 18 (18 Seume Street) with his parents, Sigismund, a postal official, and Margarete Cieslewicz (née Pohl). A document in his RuSHA file shows that he was a member of the Hitlerjugend (Hitler Youth) from 1 August 1933 to 9 June 1940. One can imagine that being in the Hitlerjugend for that long in Berlin probably led to strong views about the Nazis.

In the document, Cieslewicz gives the correct day and month of his birth, but mistakenly gives his year of birth as 1943 instead of 1921, an understandable mistake since he wrote this Lebenslauf in 1943. Hans-Dieter further states that he was born in Berlin, the son of Sigismund and Margarete, and from the age of six, attended grade school in Berlin-Lichtenberg. Four years later, he began attending the Jahn-Realgymnasium (Jahn Secondary School), which also was located in Berlin-Lichtenberg. Cieslewicz notes that he passed his Primareife (Primaries) in the spring of 1938. Thereafter, having applied for and taking his final proficiency test as a supernumerary official, he was assigned to the postal service in Berlin. On 4 June 1940, he took the primary test for administrators and was named as a supernumerary inspector. A week later he joined the Waffen-SS.

At the end of his handwritten Lebenslauf, Cieslewicz states that he became a member of the Waffen-SS on 10 June 1940 and was assigned to SS-Pionier-Sturmbann Dresden (SS Pioneer Battalion Dresden). This was the SS pioneer school at this time where recruits would receive several months of training and were then sent to their permanent SS units. The photo below shows Cieslewicz in 1940:

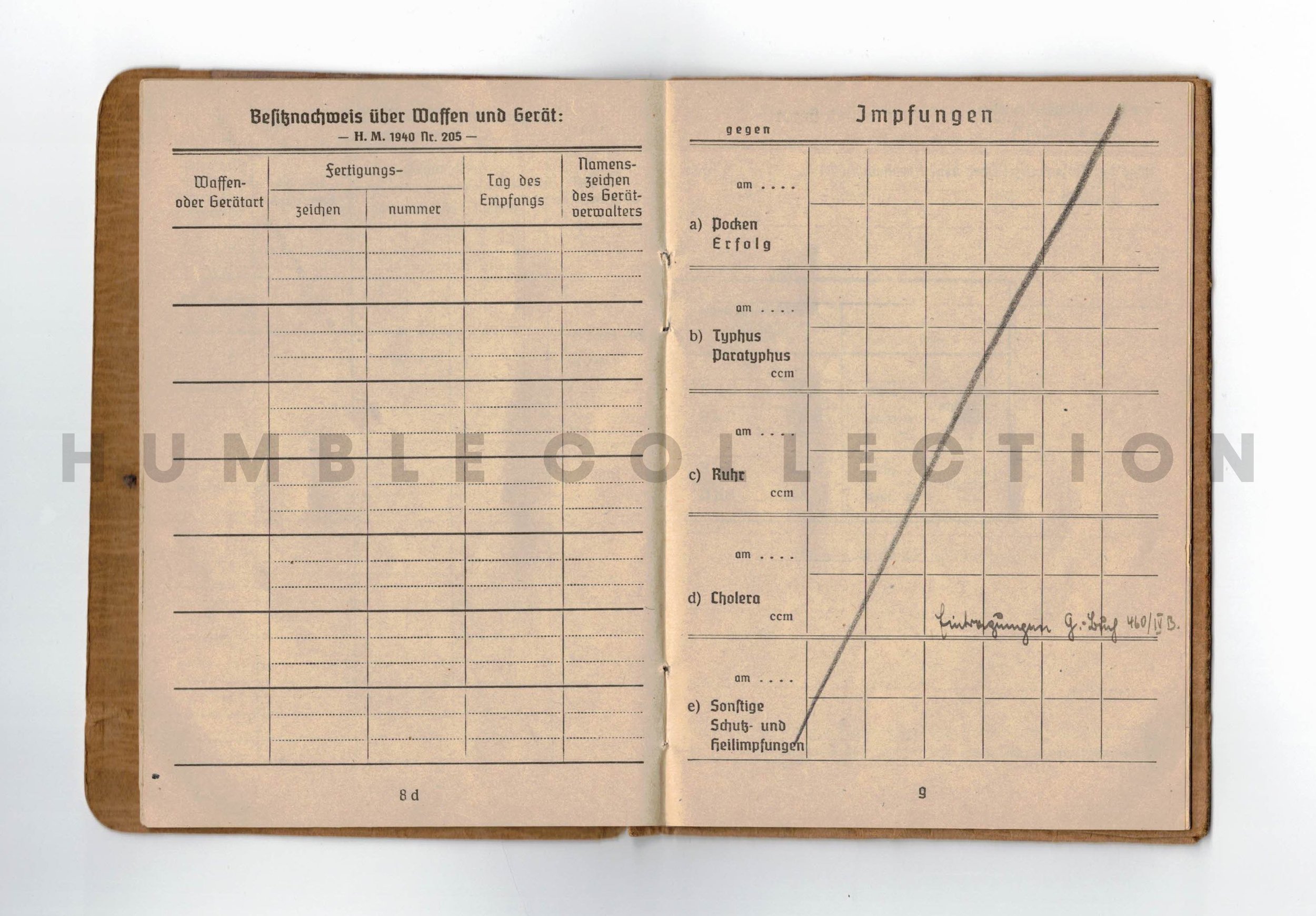

Page 1 of his Ersatz-Soldbuch shows that his Erkennungsmarke (Dog Tag) was issued to him by the “2./Pi. Btl. 1” (2nd Company of Pioneer Battalion 1), and that his unit roster number was 460. The Deutsche Dienststelle (WASt) confirmed that Cieslewicz's Erkennungsmarke (Dog Tag) Number was 460. Although the WASt could not provide the unit that issued the Erkennungsmarke, we can be sure that it was issued by “2./SS Pi. (Ersatz) Btl. 1 (Dresden)” – 2nd Company of SS Pioneer Training and Replacement Battalion 1 Dresden.

SS Division “Reich” - Balkans and the Eastern Front (1941/1942)

In late 1940, Cieslewicz was assigned to his permanent SS unit. Based on information in his file, including the Wehrmacht units that assigned his medals, the evidence points to his permanent unit being the 2nd SS Division “Das Reich”. At the time Hans-Dieter was on the Eastern Front, the division was known as SS Division “Reich”. It is possible from his promotion to SS-Sturmmann on page 21 that he started with the 1. SS Division Leibstandarte ‘Adolf Hitler’ and then transferred to Das Reich by the winter of 1941. After being stationed in France in preparation for the possible invasion of England in 1940, his first battle would have been during the invasion of Yugoslavia and the capture of Belgrade in April of 1941.

According to the documents in his RuSHA file in the National Archives, Hans-Dieter participated in the initial phases of Operation Barbarossa and quickly proved to be both a skilled and brave soldier. Based on his award entries in his Soldbuch we know that the 11th Panzer Division awarded him the EK II, EK I, and Sturmabzeichen Silber. He was also awarded 4 Tank Destruction Badges by the 2./Pi. Btl. 112 of the 112th Infantry Division. There are no dates entered with these awards, but I have been able to estimate the general timeframes based on the circumstantial evidence.

A note about the units that assigned his awards - Hans-Dieter was attached (or came under the command of) the 11th Panzer Division and the 112th Infantry Division during the Battle of Moscow 41/42. He was still an SS pioneer, but came under the command of other units for a certain duties or combat needs. This was not an uncommon practice during the war by the Germans. When a specialist was needed, or even just men needed to man the lines in a sector, they were often taken from other nearby units if other reinforcements were not available. SS pioneers experienced this from the start of the war. In the book Pioniere der Waffen-SS im Bild by J. Poll (2000 edition) on page 49, the author states that even as early as the Polish Campaign in 1939 many of the SS pioneers were transferred to infantry engineer battalions. Trained engineers were needed all over the Eastern Front in 1941 as bridgeheads were being formed. During the first winter in Russia they were even used in desperate attempts to stop the waves of Soviet tanks. Pioneers were highly valued and sent to where they were needed most on the line.

Battle of Moscow 1941/1942 (SS Div. “Reich”, 11th Panzer, 2./112th Pi. Btl.)

The article The German SS at Rzhev: Loyal to Their Deaths by Ludwig Dyck paints a picture of the struggle the 2nd SS Division “Reich” faced in the winter of 1941/42 on the outskirts of Moscow. For the SS troopers, the order to fall back on December 9 was a hard pill to swallow. Before reaching Moscow the division had already lost 60% of their strength in 1941. Even so, No. 1 Company of their Kradschützen (motorcycle) battalion had reached the end of the Moscow tramway system before the order to pull back. The men were dirty, unshaven, freezing, and plagued by lice. Through snowstorms and temperatures that sank to 46 degrees below zero centigrade, the SS troopers held their lines against an equally determined enemy. Lubricants and fuel froze, firing pins snapped, tanks refused to start, machine guns fired no more, and aircraft were grounded. As the advance came to a halt due to the Soviet resistance and the especially brutal winter, the German army fell back in order to hold more tenable position further west.

At this time, the SS Division “Reich” and the 11th Panzer Division were both part of Panzer Group 4, Fourth Army, of Army Group Centre. I am not sure if Cieslewicz’s attachment to the 11th Panzer Division happened before or during the Battle of Moscow, but the latter seems most likely. It seems that battalions and regiments of the SS “Reich” Division were pieced into the lines. For example, The Der Führer regiment fought for 3 weeks under the command of the 256th Infantry Division from late January to February of 1942.

On 29 January 1942, the Soviet 30th Army (seven rifle divisions and six tank brigades) launched their offensive. Their goal was to try and encircle the German Army Group Center between Moscow and Smolensk. The Soviets were close to accomplishing their goal, but the Germans were able to keep their main route to Smolensk open. The Soviets attacked for three longs weeks, both day and night. Obersturmbannführer (Colonel) Otto Kumm, the commander of the Der Führer regiment, described the nature of the fighting:

“The heroism of the men in those days by far exceeds anything accomplished so far. Every attack is broken at the cost of fearful casualties, often in close combat with grenades and side arms. Mounds of enemy dead pile up in front of the company positions. Most horrible of all are the attacks by enemy tanks.”

Depiction of German units almost completely surrounded in February 1942.

The division was sacrificed to blunt a Red Army winter offensive at Rzhev. Pioneers were used with the guns of Pz-Jg. Abt. 561 to fend off Soviet tank attacks. By February 3, the Pak guns of Leutnant (2nd Lt.) Peterman’s PzJgAbt 561 had tallied 20 T34s destroyed. As the tank hunting units ran out of ammunition, the grenadiers and pioneers became reliant on mines and Molotov cocktails to disable Soviet tanks.

From my research I think that it is most likely Cieslewicz destroyed 4 Soviet tanks under similar conditions in February of 1942. On 17 February 1942, Das Reich began to recall their formations from the front lines and were put in Army Reserve. Over the next couple of months the SS Div. Reich made their way to France for refitting (and in the summer of 1942 was renamed Das Reich).

The 112th Infantry Division was busy constructing defensive fortifications along their lines. Around the time that the SS Division “Reich” was called off of the frontlines, Cieslewicz apparently made his way to 2./Pi. Btl. 112 to help construct their defenses, because of the need for skilled pioneers. The 112th Infantry Division had been severely depleted of manpower like many of the other divisions along the front.

The Sonderabzeichen für das Niederkämpfen von Panzerkampfwagen durch Einzelkämpfer (Tank Destruction Badge) was awarded to individuals who had single-handedly destroyed an enemy tank or an armored combat vehicle using a hand-held weapon. The award was established on 9 March 1942, but could be awarded for actions dating back to 22 June 1941 (the start of Operation Barbarossa). For Cieslewicz to have been awarded 4 Tank Destruction Badges by the 2./Pi. Btl. 112 it would have happened between 9 March and 19 March 1942. The 11th Panzer Division awarded Hans-Dieter’s EK I, so he might have not destroyed all 4 tanks at the same time. They could have been spread throughout the campaign in the East and awarded to him once the badges became available on 9 March 1942. From Hans-Dieter’s RuSHA file we know that his last day on the Eastern Front was 19 March 1942.

SS-Sonderlehrgang z.b.V. “Oranienburg”

After returning from the Battle of Moscow, Cieslewicz was recruited and then volunteered for a secret assignment with a newly formed SS commando unit. In March of 1942, the SS created their own Special Forces unit - Sonderlehrgang z.b.V. "Oranienburg" – as an obvious rival to the Heer’s Brandenburg Regiment. In his RuSHA file dated 19 July 1943 we can see that Cieslewicz’s Feldpost number is 48312:

(20.10.1942 – 9.1.1943) SS-Sonderkommando z.b.V. Oranienburg

(10.1.1943 – 26.9.1943) Stab SS-Sonderverband z.b.V. Friedenthal

(27.9.1943 – 7.5.1944) 26.4.1944 Stab u. Einheit SS-Jager-Bataillon 502

(8.5.1944 – 5.12.1944) 24.11.1944 Fuhrungsstab der SS-Jagerverbande

(6.12.1944-8.5.1945) 16.1.1945 Fuhrungsstab u. Einheit der SS-Jagdverbande

Some of the best information I have found on the subject is in the book The SS Hunter Battalions by Perry Biddiscombe. Biddiscombe states that although it is a largely forgotten story, the original wedge for expanding the SD’s sabotage/subversion effort was born of German attempts to exploit tension in Ireland. Here is some contextual information from Biddiscombe’s book for those that are not familiar with the origins of this unit:

As the possibility of invading Great Britain subsided in late 1941, the original plans for an invasion of Ireland in cooperation with the Irish Republican Army (IRA) shifted toward keeping southern Ireland free of Allied occupation and thus denying it as a base for anti-submarine warfare in the North Atlantic. The Abwehr and Foreign Office suggested that two Wehrmacht divisions be held in readiness at Brest, France, so that they could be ferried to Ireland in case of a British invasion. This plan was rejected by the Armed Forces High Command (OKW), which had neither sufficient land nor sea forces to undertake such a mission.

Edmund Veesenmayer, the Foreign Office’s specialist in conspiratorial intrigue, advanced a more modest scheme that he discussed with the SD-Ausland. In a series of conferences hosted by the OKW’s Special Staff on Commercial and Economic Warfare, and in which navy, Luftwaffe and Abwehr representatives took part, Vessenmayer proposed that aircraft and blockade-running sea vessels be reserved in order to supply the Irish with arms in case of an emergency, and that a small SD special services company be built in order to help the Irish Army should British invaders push into Eire. In case of such a coup de main, a small IRA-German team would be landed in order to prepare Irish opinion for a limited German intervention. This detachment would also reconnoiter drop zones for a main party to follow (Sonderlehrgang z.b.V. "Oranienburg"). Several days after the dispatch of the pathfinders, the SD unit would be parachuted or landed by sea, whence it would start guiding Irish regular and irregular forces in rear-guard efforts and in the organization of partisan warfare, for which the Irish were felt to be suited by both temperament and tradition. The German specialists would also be responsible for training Irish soldiers and ‘volunteers’ with modern weapons, a supply of which would be air-dropped or landed on the coast by German vessels.

Until the middle of the Second World War, the SD-Ausland had no special services unit of the sort required for the prospective intervention in Eire. SD-Ausland regional bureau had created their own sabotage groups on a case-by-case basis, such as ‘Zepplin’ and ‘Parseval’, but the only SD subsection formally charged with supporting general sabotage activity was the supply office, Section F, which Himmler had ordered to form a guerilla-warfare and subversion directorate code-named ‘Otto’. Based at 6a Delbrückstrasse, Berlin, ‘Otto’ was run by Sturmbannführer Hermann Dörner, a former adjutant to Himmler and a rising star in the SD hierarchy. When the SD agreed to organize a formation for combat in Ireland, it was placed under the loose purview of ‘Otto’, although a large role in determining the character of the unit was played by Obergruppenführer Jüttner, the training chief of the Waffen-SS. Jüttner acted as the initial liaison with SS combat formations, from the ranks of which the unit’s men were recruited.

In August of 1942, a Dutch SS officer, Pieter van Vessem, was transferred to the SD and led one hundred Waffen-SS volunteers to an SD training ground at Oranienburg, near Jüttner’s headquarters at Fichtergrund. At Oranienburg, the men cooled their heels for over a month, not being informed of their mission, until Dörner finally arrived and launched preparations for operations in Ireland.

Some of the only documents that still exist today in the German archives for Hans-Dieter Cieslewicz come from the RuSHA (Rasse und Siedlungshauptamt) office. This was completed for his application to marry Christel Franke on 19 July 1943. Most of Cieslewicz’s clandestine history would have been lost without these files:

SS Commando training for Guerilla Warfare in Ireland (July – Dec. 1942)

Cieslewicz was one of the original 100 combat-experienced SS troops to volunteer for this new unit, although he would not become aware of their mission until September of 1942. At this time, these were all high quality and combat-proven soldiers. Obergruppenführer Jüttner’s men probably approached Hans-Dieter in July of 1942. One can imagine that his EK II, EK I, Sturmabzeichen, and four tank destruction badges stood out to the recruiters. Jüttner was in charge of finding volunteers from SS combat formations. At this time the 2nd SS Division ‘Das Reich’ was refitting in France after being decimated on the Eastern front. It makes sense that Jüttner would recruit from a combat-experienced unit like Das Reich that was being rebuilt away from the front instead of finding fresh recruits from the SS schools or taking combat-experience men from the front lines.

When the American 34th “Red Bull” Infantry Division landed in Northern Ireland on 26 January 1942, the Germans created plans for ‘Unternehmen Fischadler’ (Operation Osprey). Osprey envisioned the use of the volunteer SS commando troops trained in sabotage and British weaponry to go to Ireland in the event of an American invasion and train Irish partisans. The volunteers were taught English and became experts with British weaponry, guerilla tactics, sabotage, communications, and explosives training. Based on Cieslewicz’s future assignments, and his previous combat experience on the Eastern Front as a pioneer, he must have been particularly skilled with explosives.

Here is another excerpt from The SS Hunter Battalions by Perry Biddiscombe:

Despite the fact that the Oranienburg unit was well-trained and well-armed, two Brandenburg specialists who were sent to observe the company in November of 1942 were not impressed. When these officers, Helmut Clissmann and Bruno Rieger, showed up at Oranienburg, they explained that they had been ordered to provide English lessons and wireless instruction, although Clissmann was a close associate of Veesenmayer and was also supposed to check on the unit’s overall progress. Clissmann had lived in Ireland before the war and was considered an expert in Irish matters. He and Rieger found the three platoons of trainees in a feisty and arrogant mood, noting that with their utter contempt for all things foreign, they would not make themselves popular in Ireland. The SD troops, Clissmann later recalled, had been “too overbearing and spoilt by SS discipline for use in Catholic Eire”. He and Rieger issued a negative report, while at the same time Hitler began to reconsider the scheme because of the changing strategic situation. In conversations with Dörner, Veesenmayer agreed to make the SD unit available for other duties, and a number of Irish nationalists recruited by Dörner were released for alternate missions. In general, it was not a propitious start for a formation that was destined to evolve into the main German locus for the organization of guerilla warfare throughout Europe.

Ostmedaille awarded by “Geb. Div. Norw.” (est. August 1942)

On the awards page in Cieslewicz’s Soldbuch, it shows that he was awarded the Ostmedaille by “Geb. Div. Norw.”. There was not a Geb. Div. Norw., but there are two possible units that this could be referring to. It is either referring to the Gebirgs Korps “Norwegen”, which was stationed near Murmansk, or it is referring to the SS Gebirgs Division “Nord”.

I believe that the latter is more likely, but Cieslewicz was not fighting with them. The entry in the Soldbuch was made by Oberleutnant Müller of, what appears to be, the K-Verband on 16 March 1945. We know that on this date when the Ersatz Soldbuch was opened that he seems to of purposefully left “SS” markings out of the entries. Therefore, the SS could have been dropped off in the notation. An example of this is his dog tag entry on page one, which is shown as “2./Pi. Btl. 1” instead of “2./SS Pi. Btl. 1”. Oberleutnant Müller might have thought that he was doing Cieslewicz a favor, who at this time was a veteran Marine Oberfeldwebel der Reserve. Also, many of the Kriegsmarine men did not like serving with SS men. In November of 1944, about 50 SS convicts that were sent to the K-Verband were kicked out after an unsavory incident. A third possibility is that it was for security reasons due to Cieslewicz’s commando missions, or it could be a combination of all the reasons listed above. The SS markings that do appear in his Soldbuch were not made by Oberleutnant Müller on 16 March 1945. Even so, “Norw” is still wrong and it should be “Nord”. Stormfighter surmised in his original post that Cieslewicz probably had no personal documents on hand when his Ersatz-Soldbuch was issued, and this was a generic name from his memory. I think he was only briefly with the SS Gebirgs Division Nord for training at Oranienburg, which is when the medal was awarded to him.

After the plans for partisan operations in Ireland were abandoned, SD-Ausland decided to retain the Oranienburg Special Operations Unit as a permanent addition to its roster, controlled administratively by the SD but depending on the Waffen-SS for personnel and training. The unit was given the name Oranienburg, because that is where their training took place by the Waffen-SS. The SS Nord Division was renamed SS Gebirgs Div. Nord in January 1942 and new units began forming in Germany for the division in the summer of 1942. These new units were sent to the front in September of 1942, and the division was redesigned SS Gebirgs Division Nord. It is likely that some of these units were being trained at Oranienburg where Cieslewicz and the other commandos were stationed beginning in August of 1942. A Feldpost number was not officially established for the SS commandos until October of 1942 (48312), so it is likely Cieslewicz was awarded the Ostmedaille during while being stationed with SS Gebirgs Div. Nord at Oranienburg.

It is also curious to note that Oblt. Müller wrote down the Feldpost number 40513 on page 2 of Hans-Dieter’s Soldbuch. From 1941 to 1943 this Feldpost number was used by ‘1. Kompanie Pionier-Batallion SS-Division Nord”. Maybe the commando unit was using this same facility at Oranienburg in March of 1945 (same unit that awarded the Ostmedaille), which would suggest that Cieslewicz still had a connection to the SS commandos during his attachment to the K-Verband. This can be reinforced by his transfer to the SS Kampfschwimmer school in Bad Tölz in March of 1945 and ending the war as an SS-Unterscharführer in the 17th SS Division Götz von Berlichingen instead of with the K-Verband.

If Hans-Dieter Cieslewicz received the Eastern Front medal from the Gebirgs Korps ‘Norwegen’, then he would have been attached to the corps for a commando operation against Allied supply lines near Murmansk. Although this was a prime target with implications that could drastically impact the war in the East, I have not found any evidence of commando operations that took place. Also, the SS commandos had just arrived at Oranienburg at this time. The closest activity I could find was Operation Klabautermann, which the German Kriegsmarine and Luftwaffe conducted from Finnish bases on the shore of Lake Ladoga outside of Leningrad. Beginning on 1 July 1942, German and Italian PT boats were used to interdict Soviet traffic on the lake that was attempting to supply Leningrad. But Leningrad is a long way from Murmansk where the Gebirgs Korps Norwegen was located, so this scenario is unlikely.

SS Sonderverband z.b.V. ‘Friedenthal’

Iran, the Belgian Congo, and Otto Skorzeny (January – July 1943)

After the Irish guerilla plans were abandoned, Dörner used the new organization to train foreign agents. Cieslewicz would spend the first half of 1943 training these agents and planning for operations, many of which never materialized. Here is another passage from The SS Hunter Battalions:

In the spring of 1943, [Dörner] spent considerable time preparing twenty German saboteurs, plus Persian translators and guides, for air-drops into Iran. The idea behind this project was to stir up Iranian insurgent groups. A six-man team was deployed on 29 March 1943, with the insertion carried out by long-range aircraft from Crimea tasked by ‘Zepplin’. Two of the operatives were able to find and join Franz Meyer, an SD agent who was already on the ground, but the mission as a whole failed when its chief, Gunther Blume, was arrested.

A similar plot was developed for the Belgian Congo. With the help of Flemish fascists, a small group of missionary fathers and a few disaffected Belgian colonists, SD special forces hoped to land a ten-man ‘Vorkommando’ by U-Boat and then build up an insurrectionary army of 2,000 men. The ultimate goal was to make contact with a rebellious African tribal chief, accepting his hospitality in the bush and carrying out sabotage attacks, while a radio outpost would keep SD controllers informed about operations. Oil wells were considered an especially important target. This scheme never materialized – perhaps the notion of aiding revolutionary African tribesmen caused the racist in the SS leadership to blanch – and the Portuguese Legion, which had a base in Angola, refused a request for help.

Finally, van Vessem and company were also being trained for operations in the Balkans, but before they could be sent to this front the course of the unit’s history was abruptly altered by the appearance of the monumental figure Otto Skorzeny.

As the SS commando operation was underway in Iran, the SS decided to expand the special operations group ‘Oranienburg’ from a company into a battalion. After some political maneuvering in the ranks of the RSHA, an SS-Untersturmführer named Otto Skorzeny was chosen to lead the training and expansion of the unit. On 20 April 1943 (according to his autobiography, Skorzeny’s Secret Missions), Otto Skorzeny was promoted to SS-Hauptsturmführer and took over command of the unit. Cieslewicz states in his handwritten Lebenslauf (dated 19 July 1943) that he was promoted to SS-Unterscharführer on 20 April 1943 – the same day as Skorzeny. I’d imagine that this is the day that the Oranienburg company started its expansion and Cieslewicz was promoted due to the expected influx of new recruits. Skorzeny was very impressed with the quality of soldiers in the original company. In his autobiography he says,

“My new assignment seemed the more thrilling to me because the German war effort had accomplished only very little in this direction heretofore. Accordingly I accepted the command of all existing or future commandos. Until then, the Special Course was under the orders of a Dutch Captain, a member of the Waffen-SS. The platoon leaders of this single company were soldiers who, thanks to experience they had gained during several years of combat duty, knew their job thoroughly. Here were men upon whom I could rely; the foundations of my edifice were solid.”

Skorzeny moved the headquarters of the SS commandos a short distance away from the old Totenkopf barracks in Oranienburg to a small hunting castle at Friedenthal that dated back to the days of Frederick the Great. According the unit was renamed SS-Sonderverband z.b.V. Friedenthal. Skorzeny was very interested in making the men prepared for any mission that might arise, so he expanded the scope of their training. He talks about the extensive training in his book,

“In all candor, when I established the training program, I saw things on too large a scale. I insisted on giving my new unit as complete an education as possible in order that it might be used anywhere at all and on no matter what mission.

Each man was first to be trained thoroughly as an infantryman and an engineer; next, he was to gain at least a rudimentary knowledge of rifle grenades, field pieces [artillery], and tanks. Obviously, he was to know how to handle not only a motorcycle and an automobile but also a motorboat and a locomotive. I also encouraged all manner of athletics, especially swimming. A course for parachutists was also in prospect. Special classes were organized for men who were to be selected for special missions; their instruction included certain foreign languages and general assault tactics against enemy industrial centers.”

On 19 July 1943, Cieslewicz was with the 1st Company ‘Friedenthal’ under Hauptsturmführer Pieter van Vessem working on documentation to the RuSHA (Rasse und Siedlungshauptamt) to marry Christel Franke. She was born on 27 December 1922 in Rusdorf and living on Roonstrasse 7 in Crossen an der Oder (now Poland). Cieslewicz would eventually marry Christel Franke and they had a residence at Gudestrasse 8 in Uelzen/Hanover (this address appears in Cieslewicz's Ersatz-Soldbuch). Cieslewicz also states that he was gottgläubig (a believer in God), which would not have been popular within the SS. The page with Christel’s information also states that she was a Christian.

The 19 July 1943-dated document filled out by the RuSHA shows that by this date, Cieslewicz had earned the Sportsabzeichen (Sport's Badge), the I., II. III. Kl. (Ist, IInd and IIIrd Class) driver’s licenses, the Steuermannsschein (Coxswain’s License) and the following combat awards: the Ostmedaille, the Eisernes Kreuz II. Klasse, and the Eisernes Kreuz I. Klasse. Curiously, the Assault Badge and Tank Destruction Badges are not listed. In only four days from the time this document was filled out, Cieslewicz would begin his journey to one of the most well-known commando raids of all time.

The hunting castle at Friedenthal where Skorzeny moved his SS Kommandos in 1943 a short distance away from the old Totenkopf barracks in Oranienburg.

The Gran Sasso raid to rescue Mussolini (23 July – 12 September 1943) – Fallschirm Versuchs-Btl. III “cover” unit for SS Sonderverband z.b.V. ‘Friedenthal’

On 23 July 1943, Otto Skorzeny was called immediately to the Führerhauptquartier (FHQ). He was eating lunch at the Hotel Eden in Berlin and was told a plane would be waiting on him at the Tempelhof airport at 1700 hours. Not knowing the purpose, Skorzeny told Lt. Radl to put their two companies of commandos on alert at Friedenthal. He arrived at the Wolf’s Lair and met with Hitler around 1900 that night (7:00 o’clock in the evening). You can read more about the details of the raid in Skorzeny’s book, but Hitler decides to assign the mission to Skorzeny. Hitler told him,

“There is one more essential point,” he went on. “You must consider this the most absolute of secrets. Outside of yourself, only five persons are to be in our confidence. You will be transferred to the Luftwaffe and place under the orders of General Student whom I have already informed of this. Moreover you will see him presently; he will supply you with further details. You must yourself conduct investigations necessary to your mission. As for the military command of our troops in Italy and Rome, both must remain in ignorance of everything; they have a completely false conception of the situation and they would only act counter to our interests. I repeat then, you will be answerable to me for the most absolute secrecy.”

After being assigned the mission personally by Hitler, Skorzeny met with General Student that night to prepare a plan. Skorzeny said,

In a few moments everything was arranged: I was to fly off to Rome next morning with the general [Student]. Officially, I would be his aide-de-camp. At the same time fifty men from my shock unit were to fly from a Berlin airport to join me in Rome, traveling with the 1st Fallschirmjäger Division, which was scheduled to fly to the Italian front.

The ‘Wehrpass note’ on page 14 of Hans-Dieter Cieslewicz’s Soldbuch was the first piece of information that led me to discovering that he was one of the select few SS commandos to take part on the Gran Sasso raid to rescue Mussolini on 12 September 1943. It will not surprise me if other documents surface, but this is the only example that I know of that actually lists the name of the ‘cover’ unit that was used by Skorzeny and his men in Italy. The name of the unit was:

1. Fallschirmjäger-Division / Versuchs-Bataillon III (Experimental Battalion III)

This was a ‘cover’ unit with the Fallschirmjäger so that they would not raise any suspicions to the Italians in Rome. This fact was even hidden from Field-Marshal Kesselring. If the Italians or their secret service got wind of the plans, everything would be in vain. It is interesting that both Skorzeny and Cieslewicz’s Soldbuch confirm that the cover was with the 1st Fallschirmjäger Division, because I believe that it was the 2nd Fallschirmjäger Division that was being sent to Rome. Maybe these were replacement troops for the 1st Fallschirmjäger Division that were being sent that day.

That night (23 July 1943 – a Friday, according to Skorzeny), Skorzeny phoned his unit in Friedenthal and gave the order for fifty of his best men to prepare for the mission. Before sunrise these men would be on their way to Italy from Berlin. He gives two good accounts of this in his book:

Outside [the FHQ], the telephone rang; Lieutenant Radl was on the wire:

“What on earth is happening” he asked in high excitement. “We have been waiting impatiently for your call.”

“We are charged with an important mission. We leave tomorrow morning. I cannot give you more exact details over the telephone. Besides, I myself must think the thing over. I will call you later. For the moment, here are the earliest orders: tonight no sleep for anybody. . . have all the trucks ready because we must pick up equipment . . . I am taking along fifty men with me, our best men, that is all those that can more or less speak Italian . . . I shall draw up a list, you do the same, and we will talk over whom to choose . . . you will have to prepare colonial [tropical] equipment for everybody and parachute rations too . . . everything must be done by five in the morning.”

In a call later that night, Radl and Skorzeny compared notes for whom to bring on the mission. Skorzeny says that,

“With one or two exceptions, I found we had chosen the same names.” Radl informed him that there was a real rebellion in Friedenthal, because everyone there wanted to make the trip and not get left behind (fifty men out of roughly 500 chosen). Skorzeny told Radl to post the fifty names of those who were going to leave, and to do it quickly, to calm everyone down. This was probably around 3:00am that morning.

The fourteenth page of Cieslewicz’s Soldbuch states:

On 13 July 1943, by an order of the SS-FHA, or the SS-Führungs-Hauptamt (SS Operations and Inspection Office), Cieslewicz was assigned to Versuchs-Bataillon III (Experimental Battalion III) of the 1. Fallschirmjäger-Division.

I believe the actual date is 23 July, not 13 July. This Soldbuch entry is referring to the phone call from Skorzeny on 23 July when this order was given, meaning that Hans-Dieter was one of the fifty best men chosen for this mission. It is interesting to note the Mussolini was not arrested by the new government until 25 July, but it was clear he was on the way out of power by 22/23 July. The Germans probably had good intelligence that his arrest was inevitable.

Skorzeny also discusses some of the gear that they would bring on the mission. One interesting note for Soldbuch collectors is that the commandos were all issued Luftwaffe Soldbücher according to Radl. The gear that Skorzeny requested is important to understanding one of the reasons why Cieslewicz was one of the sixteen men (out of fifty sent to Italy) chosen to go on the raid to rescue Mussolini.

What equipment, what weapons, and what quantities of explosives would my fifty men need? Proceeding systematically, I drew up a long list. My little corps of volunteers must have the largest possible firing power yet it must transport the minimum possible weight. We might be forced perhaps to make a parachute landing; I therefore allowed for two machine guns per nine men; apart from the machine gunners, all the others would carry tommy guns. Grenades we must have too, of course – not stick hand grenades but the small grenades called “eggs” because the fit readily into the men’s pockets. Besides, we would be needing plastic explosive, say about sixty-five pounds of it; we would use the British plastic explosive which had recently arrived from Holland and which was superior to ours. Then all sorts of detonators as well as delaying models. We would need [tropical] helmets and also underwear, rations for three days on the way and three days in Italy. I immediately telegraphed this list to Berlin; then I chose from among the men who must, at all price, join our expedition.

One of the main reasons Cieslewicz was vital to Skorzeny’s operation to rescue Mussolini in Italy was because of his pioneering background. You will read that in many of Skorzeny’s missions he liked to bring along explosives. The fact that Skorzeny wanted to bring sixty-five pounds of captured British plastic explosive means that he needed to bring someone along who knew how to use it. Cieslewicz had experience on the Eastern Front as a pioneer and was probably one of the few pioneers with combat experience in the unit. He was also with van Vessem’s original commandos that were trained in British weaponry (and probably explosives for a partisan insurgency in Ireland).

Cieslewicz and Skorzeny may have also had a certain level of camaraderie. You can see in one picture the Cieslewicz is mentioned as part of Skorzeny’s “inner circle” from Gran Sasso. Skorzeny himself spent some time with the 1. SS Div. Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler (LSSAH) before being transferred to the 2. SS Division Das Reich and was present at the Battle of Moscow in 1941. Having an engineering background himself, it is possible that Cieslewicz and Skorzeny had some level of interaction within Das Reich during that time. At the very least, I’m sure the Skorzeny respected his combat bravery (EK II, EK I, Sturmabzeichen, 4 Tank Destruction Badges). After earning the EK II, Skorzeny became ill at the front and was transferred to Berlin.

When Cieslewicz and the other 49 commandos landed in Italy they were quartered in a barracks close to the Pratica di Mare airport south of Rome. Skorzeny and Student were based out of Frascati, near Rome, for the next six weeks in preparation for Operation Eiche, which it had been named. One of their first solid leads came from a German naval liaison officer on La Maddalena, Fregattenkapitan Helmut Hunaeus.

He reported that the Italian garrison on the island had recently been supplemented by a detachment of carabinieri, and new, stringent security measures were in place around the La Maddalena seaport area. But how to follow up the lead without giving the game away? Skorzeny’s ruse was to infiltrate an undercover agent – SS-Untersturmführer Robert Warger [who can be seen next to Cieslewicz in several photos], a Skorzeny commando and fluent Italian speaker, who would pose as Hunaeus’s interpreter. He would cruise the bars and cafes of La Maddelena in the hope of gaining information from the locals. In the book Otto Skorzeny: The Devil’s Disciple by Stuart Smith he says,

Warger’s modus operandi was simple. On encountering anyone who claimed to know a scintilla of information on Mussolini’s whereabouts, he would challenge him to a drunken wager on Mussolini actually being dead. By August 23, Warger’s ploy had been rewarded with a solid lead. A fruit tradesman, challenged by Warger to prove that Mussolini wasn’t dead, led him to the Villa Weber (where he made daily deliveries). There, sitting on the terrace of the house next to the villa, was the Duce himself. At the same time, Canaris (of the Abwehr), tried to convince them that Elba was a more probable location. It is said that Skorzeny was crucial to the operation in Elba being aborted. The plan for La Maddelena was approved. The plan called for a flotilla of speedboats and several Waffen-SS units stationed in Corsica were placed under his command.

Cieslewicz and the other SS commandos would be disguised as sailors on a Kriegsmarine minesweeper in the area. At the last minute Skorzeny went with Warger in disguise to La Maddelena and learned that he had been moved, so the operation was called off just in time. Stuart Smith continues:

Nearly a week passed without any news until 10pm on Sunday 5 September, when the following message was wired to Berlin: “Thanks to information obtained from a police source in the Gran Sasso area, we have discovered that the Duce is, with al probability, hold up in a hotel situated on that mountain.” This was confirmed two days later and at 9:46pm on 8 September, the order was given to proceed with the operation. The mission was on. The same evening, the Italians surrendered and defected to the Allies.

Militarily outnumbered two to one in the vicinity of Rome, the Germans were forced to act preemptively. Kesselring immediately moved the 3. Panzergrenadier Division southwards and Student’s 2. Fallschirmjäger Division northwards in a pincer movement converging on the capital. There was stiff Italian resistance, and some of Student’s paratroopers were badly mauled. Resistance only ceased on the morning of 11 September after Kesselring threatened to firebomb Rome.

Originally, Skorzeny was to have no part in the Gran Sasso raid. He was assigned to lead a subsidiary mission to rescue the rest of Mussolini’s family from the fortress-like Rocca delle Caminate outside Rome. While the final touches were being put to the battle plan, Skorzeny persuaded Student to allow 17 of his commandos to accompany him. Their role was originally not an assault role, but their task was to secure the landing zone, guard any prisoners and provide a bodyguard for Mussolini until he could be flown to safety.

In acceding to Skorzeny’s request, Student may have been influenced by what he had seen of his fighting qualities over the previous few days. Skorzeny had volunteer himself and his commandos in the ad hoc operation to secure Rome, following which he was awarded the EK I and invited to propose three of his men for the Iron Cross Second Class award.

When the Italian armistice became publically known on 8 September 1943, Cieslewicz would have been involved in these ad hoc operations to secure Rome with the Fallschirmjäger units in the area. In the pictures of Hans-Dieter Cieslewicz during the Gran Sasso raid, it is noticeable that he is the only SS commando that is wearing a Fallschirmjäger helmet. It appears to have been painted with a tan camouflage on the exterior. The Fallschirmjäger could have given him this helmet during the fighting in Rome. It is also interesting that Cieslewicz knows how to wear the helmet correctly. If you see the picture of him behind Mussolini, he has the chinstrap loose and wears in like a Fallschirmjäger veteran.

The day of the operation finally came on 12 September 1943. Student and Skorzeny were told that they could expect an 80% casualty rate for the assault. The previous weeks of fighting in Italy made them think that the Italians would put up some resistance. Skorzeny needed 16 volunteers (excluding himself and Radl) for the operation. Cieslewicz was probably thought to be essential, because of the British plastic explosive that Skorzeny wanted to bring along in case they needed to gain entry into the hotel. In Skorzeny’s book, he wrote:

Early in the afternoon of September 11, I had gone to the olive grove of a convent near Frasquati where the unit I commanded had set up camp. I had already resolved to only accept volunteers for our raid but I wished very frankly to warn them that they would face great dangers. I had them fall in and made a short harangue:

“Your long inactivity is coming to an end,” I told them. “Tomorrow we shall accomplish an operation of the highest importance, one with which I was entrusted by Adolf Hitler himself. We must all of us expect heavy losses; they are unfortunately inevitable. I shall direct our commando and I assure you I shall do all in my power; if you do the same, if we fight side by side with all our might, our mission will succeed. Let the volunteers step forward.”

To my great joy all, without exception, took one step forward. My officers had a great deal of trouble to persuade some of them to stay back because I could only take along 18 men [including Radl and Skorzeny]. On orders from General Student, the other ninety must come from the Second Company of the [Fallschirmjäger Lehr Regiment].

The other 34 SS commandos were sent to rescue Mussolini’s family from Rocca delle Caminate at the same time that the gliders were landing outside the Gran Sasso hotel. If you are not familiar with the Gran Sasso operation itself, it is worth reading about. As fate would have it, Skorzeny’s two gliders of SS commandos were the first ones to land at Gran Sasso. Although it was never the intention, he ended up leading the raid and rescued Mussolini “without firing a shot” as it became known. The Fallschirmjäger on the raid would forever resent Skorzeny for taking full credit for the operation, even though Student and his men had planned the assault.

Cieslewicz can be seen in many of the photos and film that were taken at Gran Sasso that day. It looks like he was guarding Mussolini and remained next to Otto Schwerdt as they left the hotel. You can notice the gear he carries, including what appears to be a Beretta M38/42 (MAB 38/42) submachine gun.

Photo of Kurt Student inspecting Otto Skorzeny and his men on the airstrip outside of Rome right before Operation ‘Eiche” to rescue Mussolini from the Gran Sasso Hotel.

Deutsches Kreuz in Gold for Mussolini rescue

I have spent a lot of time trying to figure out when and where Cieslewicz was awarded the German Cross in Gold by Führerhauptquartier (FHQ). The most likely scenario is that he was awarded the Deutsches Kreuz in Gold (DKiG) for the Gran Sasso raid. The main reasoning is that:

We know Cieslewicz was one of the men that took part in the raid.

We know the Skorzeny (with direct permission from Hitler/FHQ) awarded his men at least the EK I for the mission. For those that had the EK I, they were awarded the Deutsches Kreuz in Gold.

Cieslewicz’s Soldbuch shows that he was award the DKiG by FHQ (no date).

Cieslewicz is given a prominent position on the front row of the award ceremony (with those in the first glider with Otto Skorzeny) at the Berliner Sportpalast on 3 October 1943 sitting next to the officers from the raid. In a photo taken before the event, Cieslewicz is described as being part of Skorzeny’s ‘inner circle’ of Gran Sasso buddies.

We know of several SS commandos that were awarded the DKiG by FHQ that are not mentioned in lists of awardees (including Otto Schwerdt and Otto Skorzeny himself).

After the successful rescue operation, Mussolini was flown to Berlin and the SS men left their “cover unit” and returned to the commando battalion on September 15th (although they were still in Italy). Around this time Skorzeny renamed his unit. Cieslewicz’s Soldbuch shows this transfer back to the unit on page fourteen.

On 15 [September] 1943 (note the clerk errantly wrote 1944 instead of 1943), by order of Luftgau Italien/Süd (Air District Italy/South), Order Number III/17458, Cieslewicz was transferred to [SS] Fallschirmjäger-Bataillon 502 (note that the clerk made another error; the unit was actually SS-Jäger-Bataillon 502 [SS Hunter Battalion 502). It also looks like the “9” for September was purposefully turned into an “8” for August, probably to cause deception for security reasons.

When the operation was completed, Hitler himself telephoned Skorzeny around midnight. Hitler told him that he was awarding Skorzeny the Ritterkreuz and that he had been promoted to SS-Sturmbannführer. Skorzeny then spent several days at the FHQ (Wolfsschanze). Skorzeny says that after asking Hitler directly at the about awards for his men, that Hitler (award shown as FHQ in Soldbuch) gave his approval for Skorzeny to award his men how he saw fit for the Gran Sasso raid.

Skorzeny himself says that he awarded his men that took part in the raid. From the two pictures that I could find of the award ceremony, which took place soon after the raid, it confirms that everyone received at least the EK I. The soldiers (including Skorzeny) are still in their Luftwaffe uniforms and it appears that the photos were taken near the airfield outside of Rome. The men that did not have any combat experience before the raid, or did not have the EK I received it. The pictures show that at least three of the men visible on the front row were awarded the German Cross in Gold. Cieslewicz is in the back row, so we cannot see if he was awarded or not. We know that he already had the EK I and that he took part in the raid. If he were awarded, then he would have received the DKiG like the other men.

Several of the SS commandos did not have their German Crosses recorded that were awarded by the FHQ. In the photos after Gran Sasso we can tell that Otto Schwerdt was awarded the DKiG after the Gran Sasso raid, but he is not mentioned in most publications. Skorzeny’s German Cross in Gold (late 1944) is not mentioned by Scheibert, nor does it appear in Patzwall / Scherzer’s “Das Deutsche Kreuz 1941-1945”. Cieslewicz is not listed in Horst Scheibert's listing of Deutsches Kreuz in Gold recipients; however, I can cite several other examples of soldiers who were awarded the Deutsches Kreuz in Gold who are not listed in Scheibert's book as I am sure many of you ID collectors can. According to The SS Hunter Battalions by Perry Biddiscombe, Ludwig Nebel is another example of one of Skorzeny’s SS commandos who was awarded the DKiG directly by Hitler who is not listed in the records (p. 260).

Another reason Cieslewicz has not been identified as a Deutsches Kreuz recipient is because he is not wearing a single medal at the Berliner Sportpalast ceremony on 3 October 1943, even though he is given a prominent spot on the front row and is described as part of Skorzeny’s ‘inner circle’ from the raid. The possible reasons are that 1) he personally decided not to wear his medals, or 2) he had just returned from anti-partisan actions in Yugoslavia with van Vessem. I think that the most probable explanation is a combination of scenarios 1 and 2. In any case, it probably worked to his benefit to blend in and look unassuming, because his name is not found in Allied intelligence reports.

There seems to have been a certain ethos (and still is) of the original commando company that embraced the idea of ‘silent professionals’. One can notice that in every picture I have of Cieslewicz that he is not wearing any medals. Even in the film of him at the Gran Sasso award ceremony at the Berliner Sportpalast on 3 October 1943 he seems much more reserved than the men he is sitting next to. Several of these men, like Manns and Robert Warger, did not have the combat experience that Cieslewicz had on the Eastern Front. This might have been Cieslewicz’s personality (maybe like Hans-Joachim Marseille – who was known for his eccentric personality) and he was not interested in attracting attention, but it is also interesting that a Dutch Captain (van Vessem) was chosen to lead the original unit. It could be that the Dutchmen did not care for the German medals and was more interested in training commandos. In Cieslewicz’s RuSHA file, van Vessem initially forgot to mention that he had been awarded the EK II and EK I, and had to write in the awards in by hand. He also left out the Sturmabzeichen and 4 Tank Destruction Badges.

The second scenario is very interesting. Apparently Skorzeny did not have a good relationship with SS-Hauptsturmführer van Vessem (the original leader of the SS commandos). Several of the men who were on the Gran Sasso Raid – Otto Schwerdt, Hans Holzer, and Hans-Dieter Cieslewicz were taken from van Vessem’s Friedenthal First Company. It is interesting that all three were awarded the Deutsche Kreuz in Gold. Skorzeny wanted to keep van Vessem as far as possible from his center of power. While the fifty SS commandos were in Italy, van Vessem and the Friedenthal First Company were dispatched for anti-partisan operations in Yugoslavia.

One of the first things that I noticed in the Bundesarchiv picture of Cieslewicz on the front row at the Berliner Sportpalast ceremony is his combat boots that look like Gebirgsjäger footwear. The other men appear to be in dress boots. You will see that in subsequent missions in 1943 that the commandos are frequently flown all over Europe quickly. It is possible that van Vessem requested Cieslewicz to return to his unit after the completion of the Gran Sasso raid. In part this might have been a way for van Vessem to gain information about Skorzeny and what had happened in Italy. At the same time, it could have been a way for Skorzeny to keep tabs on van Vessem. Due to the nature of the anti-partisan work in Yugoslavia many of the men did not wear their medals. Cieslewicz could have finished up a mission and then flown back to Berlin for the ceremony.

Anti-Partisan missions in Yugoslavia (15 September – 2 October 1943) – 1. Komp. Friedenthal / SS Jäger Btl. 502 (mot).

As mentioned above, after the Gran Sasso raid was completed, Cieslewicz might have made his way back to his unit, the Friedenthal First Company, which was made up of the remnants of the original Oranienburg formation, still under the command of Van Vessem, before making his way back to Berlin for the ceremony as a guest of honor.

The large-scale Fall Weiss operations earlier in 1943 had failed to significantly diminish Tito’s presence in the region. These operations in Yugoslavia had already been in place before Skorzeny took over the unit. They ended up as precursor to Skorzeny operations in January of 1944 where commandos were parachuted behind enemy lines and located Tito’s HQ. The information was passed to the SS paratroopers for their raid on Tito’s headquarters in June of 1944. Perry Biddiscombe’s research in his book sheds light on van Vessem’s operations during the fall of 1943:

Such as it was, the Friedenthal Battalion had two basic duties. One was to provide raiding parties that functioned in the immediate rear of the enemy, operating from bases behind their own lines in the manner traditionally associated with commandos. One of the first places where this tactic was tried was Yugoslavia, where the Friedenthal First Company, the remains of the original Oranienburg formation, still under van Vessem, was deployed against Titoist Partisans. Van Vessem, it appears, was not a Skorzeny favorite and was dispatched far from the new centre of power. Special Friedenthal platoons were organized and their personnel disguised in civilian clothes or enemy uniforms. These ‘Trupps’ were comprised of twenty-five soldiers each, usually assembled at a ratio of two Germans to each foreign volunteer, and when deployed they split up into six-man teams that infiltrated the enemy rear and camped for three or four weeks in heavily wooded areas. Typically, the roamed freely throughout their operational areas, carrying out sabotage and reconnaissance, aided by local sympathizers. When they collected information, they returned to a central rendezvous point, where intelligence was radioed back to German-held territory and fresh targets were provided.

Further confirmation of these events by van Vessem’s unit in the fall of 1943 comes from Karl Radl’s interrogation by American Intelligence on 23 July 1945. He states that van Vessem’s 1. Company was sent to Croatia at this time.

Back to Italy – Sabotage Operations (4 October to November 1943) – SS Jäger Btl. 502 (mot).

On 5 October 1943, soon after the Berliner Sportpalast award ceremony, ten of the commandos employed in the Mussolini rescue were seconded to “stay behind” operations in Italy on the orders of Himmler.

The ‘stay behind’ operations in Italy were an attempt by the SS to launch underground resistance and sabotage operations in Italy. Himmler believed that since both the allies and axis were sitting in Italy as occupying powers, the Germans were on a level playing field and thus had finally found a forum where their attempts to launch underground resistance could potentially be as successful as those of the enemy. The potential for sabotage was felt to be good since Allied patrols were functioning mainly in the vicinity of the front, controls were lax and the guarding of supply dumps was poor. Several teams slipped through the front, most equipped with captured British demolitions, but nothing was heard back from the infiltrators, although Himmler began demanding reports on the operation.

Cieslewicz was lucky to have been sent to Italy for these operations, because the other men from the raid were sent under the command of Otto Schwerdt to Denmark where they committed many war crimes (total of 97 assassinations and 25 attempted) and became known as the Petergruppen after Schwerdt’s alias Peter Schäfer. It was so clandestine and so dark in its purpose that Skorzeny omitted it from his memoirs (and Operation Peter came close to getting him indicted for war crimes). Seven members of the group were sentenced to death in Denmark in April of 1947 and executed in May 1947. According to Biddiscombe:

On 5 October, Himmler ordered that all stay-behind operations be placed under a single chain of command, which Harster chose Kappler to run. Kappler was supposed to work with SS-Sturmbannführer Hass, a Skorzeny man who replaced the ineffective Loos, and with Obersturmbannführer Schubernig, who was given special responsibility for ‘Zer-Arbeit’ (stay-behind demolitions). Ten commandos employed in the Mussolini rescue were seconded to this new system. Nine of these men had been recalled to Berlin by late October, but the tenth, Obersturmführer Schrems, was claimed by Kappler as ‘indispensable’, although he too was eventually ordered to return to the Reich.

The reason that the Cieslewicz and the other men returned so quickly from Italy to Berlin was in preparation for Skorzeny’s next assignment in Vichy, France, but this would not be Cieslewicz’s last assignment in Italy.

Skorzeny operation – Vichy, France (20 November – 20 December 1943) – SS Jäger Btl. 502 (mot).

In November of 1943, Skorzeny was given orders from Hitler to go to Vichy, France with a company of his men. The German command had received confidential reports that friendly relations between Free France and Vichy had reached a tipping point where Marshal Philippe Pétain was actually considering seeking refuge in North Africa in order to defect to the Allies. The orders for the mission were as follows:

The purpose of this operation is to surround the city of Vichy with a cordon of troops as discreetly as possible. The detachments will be posted in such a manner as to be able, at the first signal, to encircle the city immediately so as to prevent all flight, whether on foot or by car.

Further, a second combat group must be held in reserve, This group must be strong enough to be able, at the second signal, to close in upon the city, and if the occasion warrant, to occupy the seat proper of the French government.

The troops taking part in this operation will be placed under the orders of Major Skorzeny. The Commander of the Germany Army in France and the Commander of the SS will, each in his field, place at Major Skorzeny’s disposal all means of action that he may consider necessary. As soon as the troops are in position, Major Skorzeny will report to FHQ by Teletype.

According to Skorzeny he was given two companies of men from the Waffen-SS ‘Hohenstaufen’ Division. The commander promised to send hand picked men and two of his best captains. Skorzeny says that he followed through with the promise. Wehrmacht and police units were also ready to descend on Vichy if the order was given.

The operation never materialized. Skorzeny says that there was an expression of deep disappointment that could be read on every face. It was clear that all the lads had dreamed of an exploit comparable to that of Gran Sasso. But on 20 December 1943, they received orders to drop everything and send his troops back to their units.

Cieslewicz was probably called back to take part in the Vichy operation with the other Gran Sasso veterans, but he could have also been a part of the training cadre for new Italian sabotage agents. The fact that he was sent back to Italy on 1 January 1944 makes this a possibility. According to Biddiscombe:

In September 1943, Skorzeny’s sabotage schools were once again opened up to Italian volunteers, some one hundred of whom were trained over the course of the following year. These men came from the security organs and armed forces of Mussolini’s new ‘Social Republic’, particularly the GNR and the Harbor Militia. The commander of the latter, General Visconti, seemed especially willing to hand over men to the SD. Many of these ‘volunteers’, however, were not suitable for deployment behind enemy lines, and even though some substandard recruits were weeded out during the screening process in Italy, Skorzeny and Radl were left grumbling about the poor quality of the students reaching their facilities. The trainees showed up late; their papers were not in order; and the southerners amongst them were thought to be looking for a roundabout means of returning home. Worst of all, they frequently complained that they had been inadequately informed about German expectations and that they would not undertake sabotage assignments ‘in distant territory’, something they claimed to have explained to their recruiters in Rome. SD officers in Italy responded by saying that they had taken great pains to make clear the nature of sabotage operations, and Kappler groused that his volunteers were ‘being treated in the wrong way, especially the officers.’

In January of 1944, the first cohort of Skorzeny-trained saboteurs arrived in Rome and a truckload of special fuses and explosive material concurrently arrived from Berlin, so Kappler was able to launch his initial infiltrations into Allied-occupied territory. During Karl Radl’s interrogation on 23 July 1945, he stated that 75 Italians were sent to the school during this time (three classes), but that they were unsatisfactory and only one class completed the training.

Sonderunternehmen ‘Anzio’ (1 January – 16 March 1944) – Fallschirm Versuchs-Btl. III “cover unit” for SS Jäger Btl. 502 (mot).

On page 21 of Cieslewicz’s Soldbuch it shows that he was promoted to Oberjäger (III/1. Fallsch.Jäger Div.) on 1 January 1944. This is another reference to the ‘cover’ unit that was used during the buildup to the Gran Sasso raid in Italy - 1. Fallschirmjäger-Division / Versuchs-Bataillon III (Experimental Battalion III). In reality he was still an SS-Unterscharführer with the SS Jäger Btl. 502 (mot).

Himmler was demanding evidence of vigorous activity by German special forces in Italy. Cieslewicz’s experience in Italy (he probably also spoke some Italian) and his expertise as an M and S-boat coxswain would be put to the test. The information about this operation is stored at the Bundesarchiv (R 58/471) from documents that were captured by Czechoslovakian partisans in 1945.

Under the oversight of the SD representative in Rome, Obersturmbannführer Herbert Kappler, several of Skorzeny’s officers developed a scheme called Sonderunternehmen ‘Anzio’, which involved blowing up the staff headquarters of the Allied theatre commanders, Mark Clark and Harold Alexander. A tank repair shop was specified as a secondary target. With Himmler pushing the pace of preparations, Obersturmführer Tunnat assembled four Friedenthal parachutists under Leutnant Lammers, although the operation was confounded by an array of problems. One of the squad members was injured in training and Tunnat had difficulty in procuring a special boat so that he could approach the target by sea. He also had trouble finding British uniforms with which to clothe his assassins. Three attempts to launch the team’s boats were ruined by rough seas, but a fourth try, on the evening of 8 March 1944, succeeded in getting the dinghy into the water. However, the crew of the German patrol boat that had launched the small craft later heard an explosion and saw a fireball rise into the sky over enemy-held territory. They assumed that the team’s boat had been spotted and machine-gunned by Allied sentries, and that this salvo had detonated the commandos’ supply of explosives.

It appears that Cieslewicz was not on the sabotage team that night (the fourth try). Other references state that there were as many as 8 or 9 attempts. Maybe Cieslewicz was the Friedenthal parachutist that was hurt in training and was on the patrol boat that night instead. In less than a week from the date of the failed operation, on 16 March 1944, Cieslewicz was ordered to the Kriegsmarineschule (Naval School) in Swinemünde to attend a Sprengboot-Ausbildungs-Lehrgang (Explosive-laden Speedboat Training Course). This was the period when Germany began forming Kleinkampfverbände (Small Combat Units “KKV”) to attack enemy naval forces. The explosive-laden speedboats were known as "Linse" boats.

K-Verbände and SS Kampfschwimmer Instructor / Saboteur (April 1944 – March 1945)

After the failed commando raid on 8 March 1944 to assassinate the Allied theater commanders on the Anzio beachhead, Cieslewicz was one of the SS commandos that were sent by Skorzeny at the request of Himmler to undertake “sea commando” training. According to page 14 of his Soldbuch, the order was given on 16 March 1944 to attend a Sprengboot-Ausbildungs-Lehrgang (Explosive-laden Speedboat Training Course) at the Kriegsmarineschule (Naval School) in Swinemünde on 1 April 1944.

After their initial training, Heye decided to keep the men who had been sent to training to run combat missions, help develop K-Verbände projects, and to work as instructors at the training schools. Heye also sent this request to the Brandenburg Regiment of the Abwehr for instructors, because of their previous experience with maritime commando excursions.

The Kleinkampfverbände der Kriegsmarine (KdK or K-Verbände) was the maritime counterpart to Skorzeny’s commando forces on land. By the summer of 1943 the Kriegsmarine high command turned to targeted sabotage missions as a means of offsetting their losses. The mastermind of this Kleinkrieg strategy was Admiral Hellmuth Heye. The KdK was officially constituted on Hitler’s birthday, 20 April of 1944. According to Stuart Smith in his book Otto Skorzeny: The Devil’s Disciple, Heye needed men and equipment from Skorzeny’s unit for the fledgling KdK:

Skorzeny later professed admiration for Heye as ‘a seaman in the best of the word and a first-class tactician’. Yet they were improbably bedfellows. Heye came from just the sort of traditional Prussian background that Skorzeny despised. While Heye seems to have genuinely respected Skorzeny’s relentless vitality and willingness to challenge conventional military thinking, his real reason for wanting to collaborate was more complex and cynical. On the one hand, he needed recruits for what were effectively suicide missions (totaleinsatz), and inefficient volunteers were forthcoming from the Navy [did not want to take men from the u-boats early on]. Skorzeny, he rightly felt, could help to supply this deficit with suitably motivated SS men. On the other, according to Radl, ‘he wanted to use Skorzeny for procuring the necessary material for the KdK training schools’, exploiting Skorzeny’s much-vaunted hotline to Himmler and Hitler.

In February of 1944, Skorzeny took a trip to Italy to see the Italian X-MAS Flotilla under the command of Price Borghese in action. The Italian ‘frogmen’ were some of the best in the world – accomplishing successful raids on Allied ships in the harbor of Alexandria and chief dock at Gibraltar. Cieslewicz and the other handful of SS commandos in Italy could have been present with Skorzeny during the Decimas ‘X-MAS’ demonstrations, which is why they decided to attempt the small boat raid a month later in March of 1944 at Anzio. Skorzeny noted in his memoirs:

Among the weapons presented to me, I noticed especially a small motorboat crammed with explosives, directed by a single man, who, when he neared his objective, was literally ejected and projected into the water…

One day I received orders to make contact with Vice-Admiral Heye, commandant of the “special units” which the German Navy had just created. At Himmler’s express desire, the best-qualified men in my battalion were to take part in the training given these “sea commandos.”

Cieslewicz was part of a group of 12 men originally sent by Skorzeny. There was another group that Karl Radl suggests was an initial group of 20 to 30 men from SS Jäger Btl. 502 that were sent. Radl believes that 6 of these men were killed in K-Verbände operations attacking Allied shipping at Normandy in 1944 – a 20-30% fatality rate in three months. It is possible that Cieslewicz was an active participant at Normandy with the K-Verbände in Sprengboot operations. Skorzeny mentions, “With these Linsen we executed several successful raids in the Mediterranean and especially in the English Channel, against the concentrations of ships near the beach heads in Normandy.”

Although Skorzeny originally sent his ‘best qualified men’ for this ‘sea commando’ training, he doesn’t give the full story. It appears that everyone that he sent to the K-Verband after this initial influx were SS convicts (up to 150 men). Radl even suggests that convicts were selected at first and an NCO from Jäger Battalion 502 was placed in charge of each group:

On Himmler’s orders only convicted soldiers on probation were used at first. They had to participate in a three to six week screening course at the Leibstandarte Barracks, Berlin-Lichtenfelde, at the end of which 25%, 150 men per course, were selected for KdK training. One NCO from Jg Btl 502 was place in charge of each group of six to eight men.

From extensive research, it appears that Cieslewicz was part of a group that was selected to help build the program, work on experimental craft, and have an instructor role. On the other hand, the large group of convicts with NCOs (who were not convicts) that were placed in charge of them seemed to mainly go to the Kampfschwimmer and one-man torpedo groups. After an ‘unsavory’ incident with one of the SS convicts, the Kriegsmarine volunteers became aware that they were working with criminals, which led to the expulsion of all SS convicts from the K-Verband in October/November of 1944 (those who had not already been killed). Obviously, Cieslewicz was not one of those that were expelled. The brave Kriegsmarine sailors had volunteer for this near-suicidal assignment to serve their country, but they felt that the SS convicts were sent there as punishment – which really did not sit well.

Cieslewicz’s group is more specifically mentioned in Gerhard Bracke’s book Die Einzelkämpfer Der Kriegsmarine on page 131,

The former submarine commander received valuable support from 12 Skorzeny men assigned to him, members of the Waffen-SS who were “veteran warriors with a lot of war experience” who helped him very well in these days. They were “absolutely loyal to the Navy.”

He goes on to say that it was only after the war that it became known that these men were SS-convicts who were sent there as a prison sentence, and that, on the other hand, the Navy insisted on it’s people to have impeccable character. In reality, this group of 12 were not convicts, but due to the overwhelming majority of Waffen-SS men being convicts that were sent, the 12 highly-skilled commandos are generally thrown into the same group in historical writings as the SS convicts (who accounted for over 90% of the men sent to the K-Verband – so it is understandable). It appears that Cieslewicz’s worked with the Sprengboote during his first K-Verband assignment.

Sprengboote, or literally ‘explosive boats’, were named Linsen (the word in German means ‘lens’ or ‘lentil’). Helmut Blocksdore in his book Hitler’s Secret Commandos describes these Linsen in more detail:

In the Second World War it was not the Kriegsmarine but experts of Brandenburg Regiment zbv 800, a special unit of the German Abwehr, which took up the concept…In 1941 the Army Weapons Office (Heereswaffenamt) ordered the production of explosive boats similar to the Light Assault Boat 39 built of light spruce. These were the forerunners for the later Linsen of the Kriegsmarine.

In February of 1942, Regt Brandenburg zbV 800 set up a maritime unit with the cover name ‘light engineer company’ (Leichte Pionier-Kompanie) aboard the sail training brigantine Gorch Fock moored in the Osternot harbour at Swinemünde. . . After successful completion of induction training the company – or individual squads – were deployed in various theatres of war. At the end of 1942 at Langenargen on Lake Constance the Brandenburg coastal infantry unit (Künstenjäger) was formed from the ‘light engineer company’ and other elements from the regiment. The Künstenjäger was composed of four companies, and included the explosive-boat pilots.

After the K-Verband came into existence, Admiral Heye applied for the boats to come under K-Verband jurisdiction. They took charge of the 30 Linsen that existed. Brandenburger Major Goldbach, the inventor and leader of the Linsen units, was transferred to the Kriegsmarine and given the equivalent rank of Korvettenkapitän. . . The K-Verband soon discovered that the Brandenburger explosive boats were too light for sea service, and an improved Linse was developed by ObltzS F.H. Wendel, head of the K-Verband Design and Testing Bureau. In 1941 Wendel had designed for the Luftwaffe parachute arm a 10-metre long motorboat capable of being dropped into the seam from a GO 242 heavy gilder.

This is one of only two mentions of Swinemünde that I have found in the various histories of the K-Verbände, which is where Cieslewicz was assigned. It appears that some of the Linsen infrastructure that had been built by the Brandenburgers there was still intact. Cieslewicz was transferred into the Kriegsmarine on 1 July 1944. His training unit is stated on page 4 of his Soldbuch as Schiffs-Stamm-Abteilung II Swinemünde. Specifically, he was assigned to the Lehr und Versuchsabteilung (Instructional and Experimental Detachment) of this unit. I am not sure if the “II” is referring to Abwehr II (sabotage). This is also listed on his next training unit with the Marine Schule II – Bad Tölz – Kampfschwimmer Kompanie/Kommando (KsK). The Instructional and Experimental Detachment most likely had close ties with the Regt Brandenburg zbV while Cieslewicz was there. It is possible that he worked on the redesign of the Linsen as a test pilot and worked as an instructor for Linsen and assault boat pilots. His commando background, pioneering expertise, and previous m and s-boat training would have been highly valued.

After Cieslewicz completed Sprengboot training and was assigned to Schiffs-Stamm-Abteilung II Swinemünde, he probably used this as a home base for marine combat operations with German naval sabotage units (Marineeinsatzkommandos or MEKs). The MEKS were moved to different places, like Swinemünde, as needed and were augmented with Kampfschwimmer and other commandos (depending on their mission). As commando and sabotage troops the MEKs operated behind enemy lines close to the coast, attacking harbor installations, bridges, ships, supply depots, ammunition dumps and other worthwhile targets. His specific unit within the MEK was possibly an assault boat crew. Helmut Blocksdore (Hitler’s Secret Commandos) says about the K-Verband assault boats:

The daring activities of the assault boats and their crews remain obscure. Few details and facts have emerged from the period. Most men of these units fell in action, were murdered by partisans, or failed to survive captivity in Eastern Europe. The War Diaries were destroyed or have been lost. Therefore, very little knowledge of their operations has been preserved. Additionally, the history of the assault boats is allied closely to that of the frogmen (Kampfschwimmer) and naval sabotage units (MEKs) and cannot always be separated out.